- Stratagem

- Posts

- 🌊Deep Dive Weekly Edition #3🌊

🌊Deep Dive Weekly Edition #3🌊

🚀 U.S.-China Collaboration in Space: Soft Power Potential in the New Space Race 🛰️

📚The TL;DR📝

China National Space Administration (CNSA): Founded in 1993, CNSA is headquartered in the Haidian district of Beijing, with Shan Zhongde serving as the Administrator since January 2025.

China is notably absent from the list of signatories of the Artemis Accords, which NASA and the State Department established in 2020 to promote a responsible approach to 21st century space policy.

The United States’ Artemis Program and China’s International Lunar Research Station are each working to develop a permanent base on the moon.

The United States and China, despite mutual mistrust resulting from anti-satellite weapon threats and the risks of technology transfer, possess two potential areas for collaboration: space traffic management and rescue operations.

Dominating the 21st century competition to lead the emerging space order will require a willingness to cultivate lasting partnerships with other nations reaching toward the stars.

📌🚀U.S.-China Collaboration in Space: Soft Power Potential in a New Space Race🛰️📌

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) welcomed Finland as the 53rd signatory of the Artemis Accords in January 2025, with former Associate Administrator Jim Free reiterating the United States’ commitment to a generation of space governance focused on shared exploration goals, safe and free operations, and preservation of the global commons. NASA and the State Department established the Artemis Accords in 2020 alongside seven other nations, grounding 21st-century space policy in the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. The treaty and the accords prioritize responsible behavior in space including avoiding harmful interference and limiting orbital debris. This series of non-binding multilateral principles reinforces the values of the U.S.-led international order prescribing peaceful activities in compliance with international law.

Although the Artemis Accords underscore cooperation and civility as guiding principles for space diplomacy, China—an important bilateral partner for the United States and a rising superpower in developing both technological prowess and political influence in space—is notably absent from the list of signatories. China is expanding its soft power in what lawmakers are calling a new space race. Soft power is defined as a “country’s ability to influence others without resorting to coercive pressure.” China’s inclusive and cooperative strategy towards winning this new space race has bolstered Chinese soft power. In contrast, the U.S. Congress passed the Wolf Amendment in 2011, a law prohibiting NASA from directing federal funding toward cooperation with China due to espionage concerns. As a result, U.S.-China collaboration in space has effectively ceased. With the exception of the use of NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to monitor China’s moon lander during its Chang’e 4 mission in 2019, the Federal Bureau of Investigation has barred NASA from engaging with Chinese lunar samples or experiments.

👀A Common Vision for Lunar Governance🌕

The United States and China share a long-term goal for space exploration — developing a permanent lunar base. NASA established the Artemis program in 2017 through Space Policy Directive 1, which expressed the intent to build a permanent lunar base to facilitate human missions to Mars.

The program aims to employ a series of annual missions involving the launch of a Space Launch System (SLS) vehicle carrying an Orion spacecraft. NASA successfully launched Artemis I, the first uncrewed test of these systems in 2022, with plans to launch Artemis II, the first crewed test flight, in 2026. Subsequent missions will focus on delivering more complex modules to the lunar surface, incorporating the technologies of partners such as the European Space Agency.

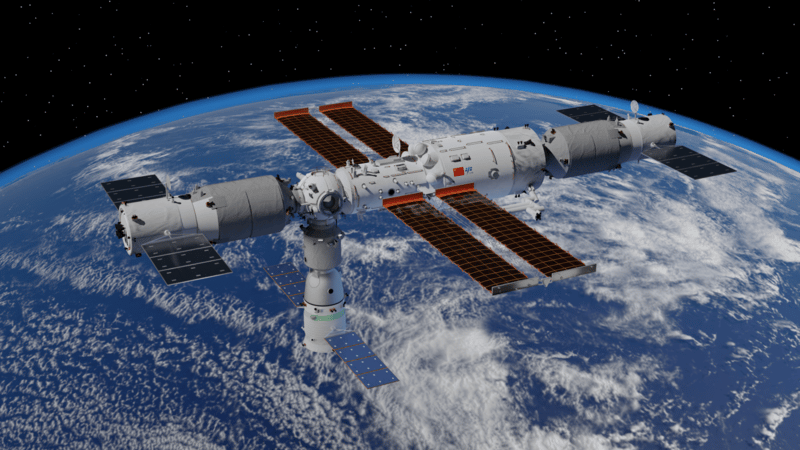

In response to the Artemis program, the China National Space Administration (CNSA) and Russia’s State Corporation for Space Activities signed a memorandum of understanding in March 2021 to jointly construct the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), an alternative to the Artemis program.

Construction will begin in 2028, following CNSA’s Chang’e-8 mission, a robotic mission that will establish the technical base for the ILRS. The two agencies underscored that participation in the project is open to “all interested countries and international partners.” Thirteen nations, including Belarus, Nicaragua, and South Africa, have since joined, with Venezuela agreeing to provide access to ground stations for optimal launches.

👨🚀Barriers to Space Cooperation: Commercial Proliferation and Soft Power Competition🛰️

The main barriers to collaboration reflect the broader strategic concerns of both countries. Anti-satellite weapon threats and the risks of technology transfer have constrained opportunities for Sino-American cooperation in space despite the two superpowers’ shared aspirations for leading the development of a future lunar society. The proliferation of commercial satellite technology in a growing market for data has only increased concerns from U.S. policymakers, who fear that Chinese space technology could facilitate cyberattacks on U.S. infrastructure in space and on the ground.

China’s commercial space industry has grown to over 400 enterprises, with a projected worth of over $900 billion by 2029. Prominent companies within the sector include the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, iSpace, and CAS Space. China’s commercial space sector works closely with CNSA to fulfill state goals in lunar governance, manned exploration, and scientific experimentation.

The rapid progression of commercial low-Earth orbit (LEO) development has begun what scholars frame as a “second space race,” in which the United States and China are competing to not only use space technologies to achieve economic and military ends but also assert leadership in governing the Moon and other planets. With 139 members and accounting for 40% of global Gross Domestic Product, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Spatial Information Corridor partners with a wide range of developed and developing countries in establishing satellite infrastructure for communications and research. Member states include close U.S. partners, such as France, Italy, and Brazil. President of the People’s Republic of China Xi Jinping’s strategic emphasis on including developing countries transcends China’s space strategy, underscoring China’s prioritization of soft power as a key tool of state operations.

China and Russia, among other countries, have criticized the U.S.-centric nature of the Artemis Accords, which permits resource extraction by U.S. commercial entities, as inconsistent with the global commons focus of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits states from extracting resources in space. However, leading scholars at U.S. think tanks including the Council on Foreign Relations argue that the benefits of cooperation with China in space outweigh the costs.

Beyond the competition for leadership in the space order, space diplomacy significantly impacts the protection of the global commons. There is no unified governance structure for the moon, except for the 1979 Moon Treaty. Neither great power is a signatory to the treaty, and although the Outer Space Treaty banned resource expropriation, the Artemis Accords established a framework for mining on the Moon. Innovation is outpacing governance; while the United States and China have expressed the desire to establish permanent lunar bases by the 2030s, the two countries have not discussed potential frameworks for lunar governance and resource protection.

However, the possibility of cooperation in space in areas of mutual interest such as lunar governance is not entirely fruitless. After China’s Chang’e-6 spacecraft successfully returned the first-ever samples from the Moon’s far side in July 2024, Chinese scientists willingly offered U.S. scientists the opportunity to analyze the lunar rocks. While talks to obtain these samples eventually fell through in November 2024, the existence of such an opportunity indicates China’s belief that collaboration on space exploration is feasible despite strategic tensions between the two powers.

👨🚒Areas of Potential Collaboration: Rescue Operations and Space Traffic Management🚀

Even with blurred distinctions between civil and military activities in both countries, the United States can engage in cooperation with China without harming national security interests. Two areas of collaboration point to common objectives despite mutual mistrust: rescue operations and space traffic management.

First, the United States and China are both signatories of the 1968 United Nations Rescue and Return of Astronauts Agreement, which enforces the assistance of astronauts in distress regardless of their origin country. The absence of specific procedures for implementing joint rescue efforts offers a starting point for opening a bilateral dialogue between the U.S. and China to discuss action plans and exchange information during rescue operations.

Second, the rise of communications satellite systems such as Elon Musk’s Starlink, along with planned systems such as China’s G60 and Amazon’s Project Kuiper, which use huge “constellations” of satellites orbiting in low-Earth orbit (LEO) to deliver Internet access, underscores the necessity of developing common rules for space traffic. Rocket launches also run the risk of creating massive fields of space debris, with one Chinese rocket breaking up into hundreds of individual pieces of debris in 2022.

These breakups risk creating “Kessler syndrome,” proposed by Donald Kessler in 1978, where space debris enables the possibility of unintended military escalation by driving a chain of debris collisions. Repealing the Wolf Amendment, which prohibits NASA from directing federal funding towards cooperation with China, can encourage NASA and CNSA to establish continuity procedures in the event of collision thereby reducing the risk of misinterpreting accidental satellite collisions as military threats.

As middle powers, developing countries, and commercial entities join the rapidly growing space technology sector U.S. collaboration with rivals in space will play a growing role in the well being of people around the globe. Space-based systems such as GPS not only provide critical data for navigation but also serve as the foundation for current agricultural planning and international disaster relief efforts.

In an increasingly digitized age, access to space provides crucial connectivity to Internet services—particularly in remote areas—with 150 million people globally expected to rely on satellite-based Internet access by 2031. Protecting global welfare while promoting U.S. leadership in space will require a greater attentiveness to U.S. soft power and a commitment to building lasting relationships with current and potential allies.

Not a subscriber? Click here to subscribe!

See You Next Tuesday For 🌎The Beyond Borders Brief!🌎

This week’s newsletter brought to you by the Deep Dive staff. Connect with us on social media to pose questions, comments, or feedback. Click here to learn more about TSI.

Reply